You probably think you know human anatomy pretty well: The average adult has 206 bones, about 650 muscles, and some 18 feet of intestines. But what if we told you that wasn’t necessarily the case?

There’s actually a surprising amount of variation in the body parts average people have. Of course, you’re probably aware of some vestigial body parts, like wisdom teeth, that the human body doesn’t really need. (The appendix used to be in this category, but the evidence continues to build that it actually has an immunological function.) But did you know there are several muscles in that category as well? Most of them are functionless. And some people—maybe even you—lack them entirely.

When these muscles disappear, it’s just standard genetics at work: A mutation causes people to be born without them, and because the muscles aren’t in use, you might not even notice. That’s why vestigial muscles often disappear within small populations. Here’s a look at what you might be missing.

1. OCCIPITALIS MINOR

This thin banded muscle located just under the back of your skull allows you to move your scalp slightly. That’s not a move that’s in great evolutionary demand these days, so it’s unsurprising that it’s managed to disappear completely in some populations. All indigenous Melanesians are born without it, as well as about half of all Japanese people, and a third of Europeans. In the deep past, this muscle would’ve been used by our mammalian ancestors to move their ears and better detect the sound of predators—but by this point, it’s essentially nonfunctional, which is why no one misses it when it’s gone.

2. PALMARIS LONGUS

This thin tendon attaches to the bottom side of the wrist and is missing in about 16 percent of people in a recent study. It’s so weak that it has no substantial effect on grip, and if it’s removed or cut, it doesn’t cause any motility changes. This quality makes it an ideal choice for use in tendon grafts because it can be used as a substitute elsewhere in the body without any problems.

To see if you have it, hold your arm out, palm facing upwards, and close your hand so that you can press your thumb between your middle and fourth fingers. If it’s there, the tendon should pop out of your wrist slightly, similar to the photo above (though maybe not as pronounced).

3. PYRAMIDALIS

Twenty percent of people don’t have the triangle-shaped pyramidalis muscle in their abdomens, although most humans have two. The function of the pyramidalis—tensing the linea alba—accomplishes little; the linea alba is mostly connective collagen that nets the abdominal muscles together. Unfortunately, it’s hard to test whether you have this or not (it is, after all, not doing much), but if you ever get surgery or an MRI, you might want to ask about whether you have it.

4. STERNALIS

Almost everyone lacks a sternalis muscle. It was only comprehensively documented when a series of mammograms in the early 1990s showed six women (out of 32,000) had an irregular structure in their chests which—after surgery on one woman and imaging on the other five—turned out to be the muscle in question.

It’s so rare, in fact, that little is known about it. It runs vertically along the edge of the sternum, on top of the pectoral muscles, but its function remains unknown. Around 8 percent of humans are believed to have them, but again, there’s no easy way to know whether you’re in the club. One theory is that it represents what’s left of the panniculus carnosus—a muscle that controls skin movement in animals, allowing, for example, grazing animals to “twitch” their body to shrug off birds and animals like the echidna to roll into balls.

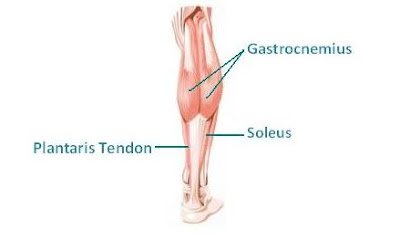

5. PLANTARIS

Found in the leg, the plantaris muscle is about 2–4 inches long and found in the very top of the leg, where it slightly aids you in flexing your knee—but not to such an extent that you can’t live without it. The tendon (if you have it) is the longest in the human body.

As much as 10 percent of the population may be missing it entirely, and while it doesn’t cause huge amounts of trouble, there is some bad news: It’s quite useful in surgery because the length of the tendon makes it a prime candidate for use replacing other tendons in the body. So if you’re one of the 10 percent and have an injury that requires surgical replacement, the donor tendon will have to come from somewhere else.